A Roadside Stand (critical analysis)

“A Roadside Stand” was first published in the June 1936 issue of the Atlantic Monthly before being collected in A Further Range with the subtitle “On Being Put out of Our Misery.” Frost at one time considered the title “Euthanasia” for the poem (Thompson, 439).

“A Roadside Stand” is another quarrel over modernization. Frost resists contemporary encroachment here as he does in other poems, such as “Lines Written in Dejection on the Eve of Great Success” (1962) about the United States space program or “The Line-Gang” about the telephone.

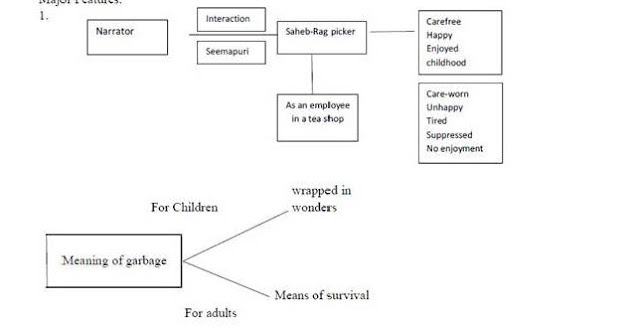

The roadside stand is a sad symbol of a past that is fading rapidly. As it is depicted, it is also evidence of a decline in agricultural prosperity. The roadside farm stand is characterized as a person selling berries, almost pleading with the people who drive by to make a purchase. The poem begins with the “little new shed” and traffic speeding by. The folks at the stand are hopeful that some “of the cash, whose flow supports / The flower of cities from sinking and withering faint” will be spent on the goods at the stand. The comparison of fueling the growth of a city to keeping a flower from withering is apt, as it demonstrates that the speaker, a farmer, draws analogies to nature, not industry, to make his points.

The speaker goes on to describe the “false alarms,” when people simply use the pullout to turn their car around, ask for directions, or ask to buy a gallon of gas, even though there is no gas for sale. The “wooden quarts” contain only wild berries and “crook-necked golden squash with silver warts.”

The “polished traffic” of nonresidents only minimally and rather dismissively notices the unrefined stand signs, “with N turned wrong and S turned wrong,” and views them as marring the otherwise pastoral landscape. The “squeal of brakes” and the “plow[ed] up grass” from city folk who have taken a wrong turn and who use the yard “to back and turn around” also cause the people at the stand to be annoyed by the disruptions and “marring” of their landscape that does not bring sales. The loss of sales, despite how insignificant the purchases may be to city folk, has a significant impact on a farmer’s way of life. And the question whether it is the stand or the traffic that mars the landscape highlights the difference in perspective between the city and the country people.

The folks “far from the city” are forced to become beggars in this contrast between city and rural life, because they are made to “ask for some city money to feel in hand.” Those responsible for this decline in a farmer’s lifestyle are identified as the “party in power,” which “is said to be keeping from [them]” the “moving pictures’ promise,” the promise of affluence and glamour as portrayed by Hollywood.

In the second stanza the speaker bemoans that people are going to live in larger and larger places, places that are “in villages next to theater and store.” He imagines the consequences of corralling people in such a way, arguing that it will make everyone lazy because people will not have to think for themselves. Again, the responsible party is identified satirically: the “good-doers” (not do-gooders) and “beneficent beasts of prey.”

The city is the source of financial stability, and the country is largely dependent on the city folk to survive. This dependence causes, in the last stanza, significant misery and disappointment. The speaker can “hardly bear / The thought of so much childish longing in vain” for a car to stop. He concludes that in “the country scale of gain, / The requisite lift of spirit has never been found” and resolves that he would be relieved to “put these people at one stroke out of their pain,” hence the consideration of “Euthanasia” as a title. Then the speaker catches himself and wonders what it would be like if someone should choose to do the same to him and “offer to put [him] gently out of [his] pain.”

Several interpretations of these last lines present themselves. One is that the speaker is imagining the opposite possibility of putting city folk out of their pain. Another reading might be that the speaker, in his empathy with the country folk and their hardships, identifies with these people, seeing himself as the old world that will long be passed by and forgotten after the changing of the guard. The speaker might realize that the world sees him as behind the times, living out the rest of his days in simply trying to achieve the most basic type of functioning in an increasingly complex world. Preceding “Departmental” in A Further Range, the poem could also be read as a criticism of socialism, given its description of apartment houses and political promises that are not kept.